The Chilean Spring (Part One): Tip of the Iceberg

Major news outlets seem to suggest that the current situation in Chile is based solely on the thirty-peso price hike in the underground fare. This, however, is far from the truth. While many people – especially secondary students – found the measure incredibly unfair and started fare-dodging in protest, the underlying issues now facing Chilean citizens go back more than thirty years to the genesis of neoliberal reforms which reshaped the country into what it is today.

Following the 1973 coup, the Pinochet regime started implementing a neoliberal agenda. A group of economists trained under the tutelage of Milton Friedman at the Chicago School of Economics – known as The Chicago Boys – developed a programme to implement reform in Chile. Many of the Chicago Boys held high positions in the regime: this allowed the swift imposition of neoliberal policies on a populace shocked into submission by curfew and the unleashing of military force.

Prominent members of the Chicago Boys included Sergio de Castro, who was Pinochet’s Minister of Finance between 1975 and 1977; José Piñera – brother to current president Sebastián Piñera – who was Minister of Work and Pensions between 1978 and 1980 and the mastermind behind the privatised pension system; and Christian Larroulet, who served as Minister Secretary-General of the Presidency during Piñera’s first administration (2010-2014).

The rhetoric behind economic changes imposed during the dictatorship depicted Chile as a dying patient in need of treatment. The way to pursue neoliberalisation was straightforward, as David Harvey writes: ‘They reversed the nationalization and privatized public assets, opened up natural resources (fisheries, timber, etc.) to unregulated exploitation (in many cases riding roughshod over the claims of indigenous inhabitants), privatized social security, and facilitated foreign direct investment and freer trade. The right of foreign companies to repatriate profits from their Chilean operations was guaranteed.’ Indeed, the most radical process of privatisation in the contemporary world took place in Chile between 1985 and 1989, as Chilean analyst María Olivia Monckeberg describes.

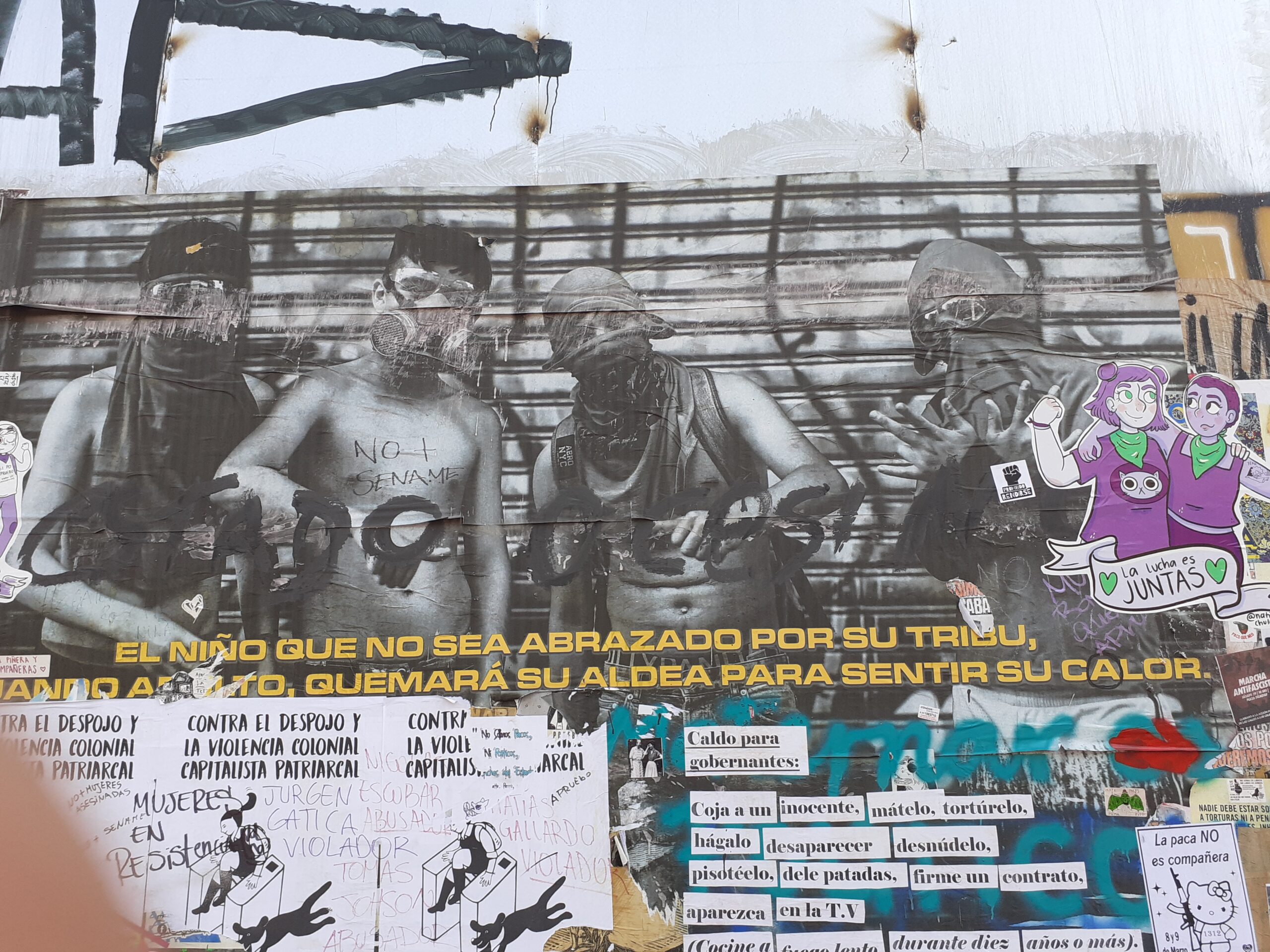

For the average Chilean, this process took place very quickly and in a way that was hard to fathom. Thousands of people were imprisoned, while many others were disappeared. Most Chileans existed in a climate of fear that shrouded what was really taking place behind the dark curtain: the neoliberalisation of the country. Those who benefitted from the looting of former state-owned companies and services were the same groups which today perceive the military and the police as armed guards whose duty is to protect ruling interests.

Neoliberalism – and the subsequent rewards it brought to a select few – was imposed on the backs of millions of Chileans who are now demanding a fairer country. In her groundbreaking 2001 book, El saqueo de los grupos económicos al Estado chileno (The Pillage of the Chilean State by Economic Groups), Monckeberg writes ‘those that worked in ministries, strategic consultancies or from within former state-owned companies that fostered [the neoliberalisation process] during the military regime are those who today enjoy the results of their work back then’ (my translation, 25). The current repression in Chile is a desperate attempt by the elites to protect the gains they have made under neoliberalism.

Chileans in general were unsure what privatisation would entail until many years after its implementation. One of the most extreme examples is around pensions. José Piñera established a system that replaced the public pay-as-you-go system for one requiring people to save a portion of their salaries each month, with their contributions subsequently invested in private funds. Today, the average pension, after a lifetime of work, is 243,000 Chilean pesos (£250). The previous state-owned pension system provided much higher pensions and the funds were distributed more evenly among the retired, rather than according to their individual contributions.

The current pension of about £250 is not enough to make ends meet. On top of such a low monthly income, pensioners are required to pay a seven per cent charge for healthcare and to purchase their own medicines. The little they receive each month fails to provide for a decent standard of living. There are many stories of pensioners wandering the streets of Santiago and other cities begging for money, selling handicrafts they have made or simply performing. One of the saddest cases was a video of a 90-year-old man skipping on a rope in order to get tips as he was unable to live off his pension. This and many other cases illustrate the precarious conditions facing Chilean pensioners, with pension reform a core element of the current protests.

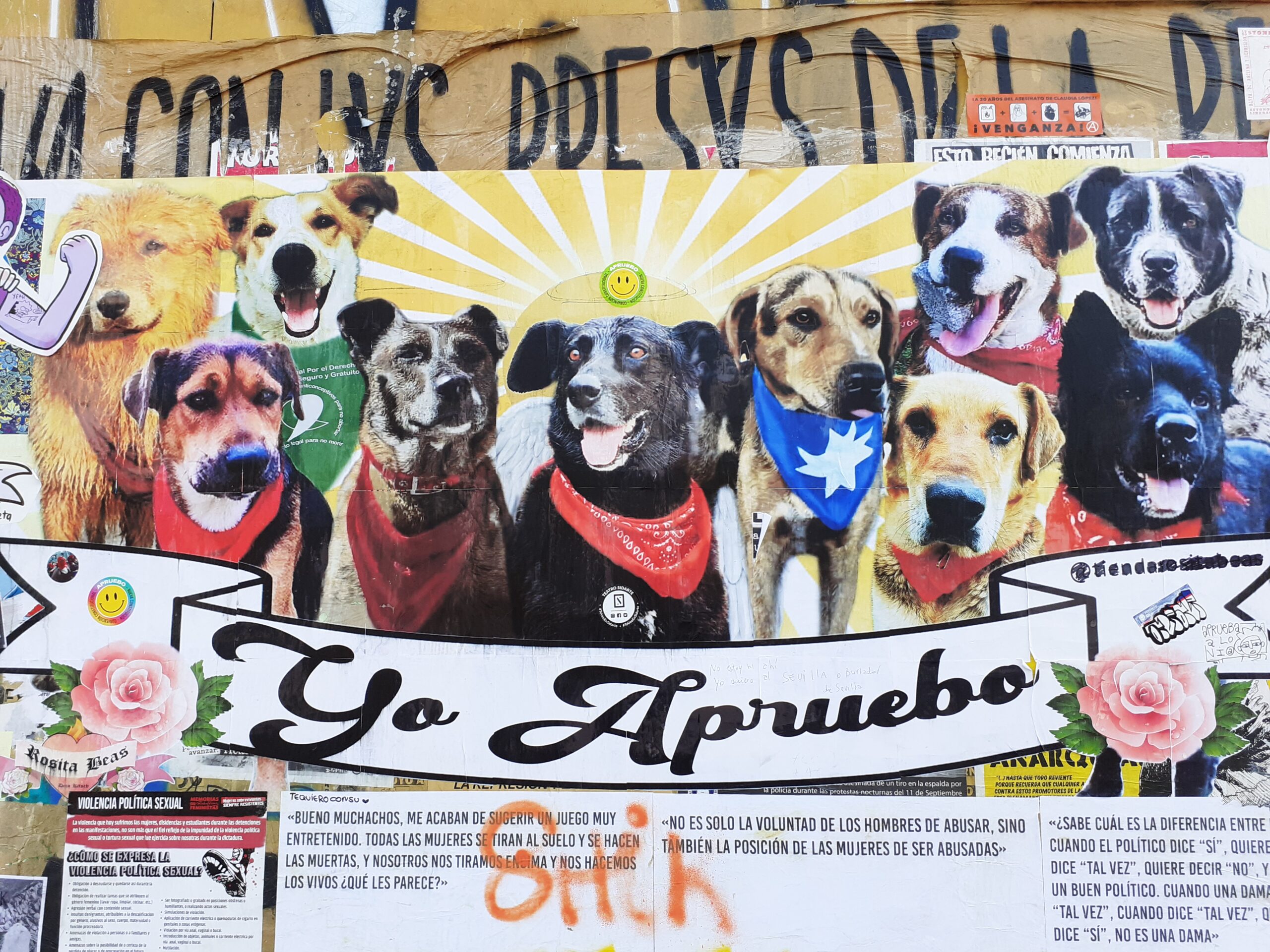

On Tuesday, President Piñera nervously addressed the country on television offering a package of social reforms to quell the protests. His proposals for pension improvements, however, were widely seen as insufficient and as failing to address the neoliberal reforms devised by his brother José during the dictatorship. There is great disappointment and anger towards the economic elite. Chileans on the streets now sense an opportunity to end 30 years of misery and lies.